How Much Does Your Energy Cost?

Some History

OPEC (The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) was founded by five nations in 1960, growing to 11 producers by 1971. The Yom Kippur War two years later saw a political split in that all nations supporting Israel after it was attacked by Egypt and Syria would be embargoed (denied their previous exported crude oil supply). Prior to this event, crude was being purchased for a long-stable price of about $3 per barrel but after the turmoil it moved quickly to $12. With the onset of the first U.S. Energy Crisis (1973), we became far more interested in how much electricity and fossil fuel our homes consumed. That is, after we learned how to cope with gasoline shortages, rationing, and price shocks.

In the years since, OPEC has not always been able to reign-in the export volumes of their members, and prices would sometimes flatten or fall. But over the years, the price of a barrel of crude has gone much higher, in fits and starts. By 1977, the race to complete the Alaskan Pipeline was on. The last hurdle to congressional approval for the project was to insure that all oil would come to U.S. refineries. That continued from the pipeline's completion until the last week of President George H.W. Bush's term in January, 1992, when, by Executive Order, the mandate for shipment only to U.S. refineries was cancelled.

In the 70's, President Jimmy Carter tried to get our nation interested in conservation of fossil fuels as a way to lessen petroleum price shocks and build a U.S. policy toward less dependency on OPEC. Few were listening. We kept buying big, fat heavy autos, and only the 1979 gasoline price spikes re-focused our attention on smaller, high mileage cars (but for too short a period). The (in effect toothless) CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) mileage standards passed by Congress were regularly delayed and bypassed for over 14 years. No longer. Mileage standards for U.S. passenger cars are now higher.

OPEC (The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) was founded by five nations in 1960, growing to 11 producers by 1971. The Yom Kippur War two years later saw a political split in that all nations supporting Israel after it was attacked by Egypt and Syria would be embargoed (denied their previous exported crude oil supply). Prior to this event, crude was being purchased for a long-stable price of about $3 per barrel but after the turmoil it moved quickly to $12. With the onset of the first U.S. Energy Crisis (1973), we became far more interested in how much electricity and fossil fuel our homes consumed. That is, after we learned how to cope with gasoline shortages, rationing, and price shocks.

In the years since, OPEC has not always been able to reign-in the export volumes of their members, and prices would sometimes flatten or fall. But over the years, the price of a barrel of crude has gone much higher, in fits and starts. By 1977, the race to complete the Alaskan Pipeline was on. The last hurdle to congressional approval for the project was to insure that all oil would come to U.S. refineries. That continued from the pipeline's completion until the last week of President George H.W. Bush's term in January, 1992, when, by Executive Order, the mandate for shipment only to U.S. refineries was cancelled.

In the 70's, President Jimmy Carter tried to get our nation interested in conservation of fossil fuels as a way to lessen petroleum price shocks and build a U.S. policy toward less dependency on OPEC. Few were listening. We kept buying big, fat heavy autos, and only the 1979 gasoline price spikes re-focused our attention on smaller, high mileage cars (but for too short a period). The (in effect toothless) CAFE (Corporate Average Fuel Economy) mileage standards passed by Congress were regularly delayed and bypassed for over 14 years. No longer. Mileage standards for U.S. passenger cars are now higher.

Today

No one needs to explain to you that energy prices have risen in recent years and that they will likely continue that trend. The question is, "Can you tolerate or afford those prices in the future?" For thermal energy (BTUs to heat your home and make your hot water) the most objective cost barometer is the measure of your cost per million BTUs. That's the money it takes to place a (net) million BTUs into your ductwork or hot water, expressed as dollars per MMBTU.

As a homeowner, you'd like to shop for the lowest cost per million as you do among gas stations for your vehicle. Unfortunately, houses are less flexible than cars in switching suppliers. Once you've got a system—you're saddled with a particular fuel choice (unless you are willing to perform multiple retrofits). So, the trick is to choose a fuel that will serve you well into the future.

Many have attempted to do that with fuels like wood or wood pellets burned in stoves. While helpful in a power outage, both of these sources face a challenge. Gathering and processing your own wood requires your time, some risk, dependence on specialized equipment, and easy access to your local national forest (where, as of Fall, 2011, local access rules for woodcutting have become near-impossible). Depending on commercial woodcutters means buying at retail, as does the purchase of wood pellet fuel.

Details on Firewood for Home Heating--

This file, called Fuelwood Facts, was written by Hugh Hansen, Extension Ag Engineer for Oregon State University. It's a 35-year old report but it doesn't emphasize pricing, so anything here is solid information, and as unchanging as gravity.

Click Here for Fuelwood Facts

Types of household heating fuel--

|

Retail Energy Commodities

and their purchase unit names Electricity (resistance) kilowatthour Electricity (air-to-air heat pump @3.0 COP) leveraged kwh Electricity (ground source heat pump @4.2 COP) leveraged kwh Natural Gas therm Propane Gas gallon Fuel Oil gallon Commercial softwood or hardwood cord |

Amount of BTUs in the Gross Purchase Unit of Each

3,413 10,239 14,335 100,000 91,500 135,000 18-27,000,000 (depending on type and moisture content) |

Of the seven examples above, the first three are relatively fixed. There are no combustion efficiencies to consider. But both kinds of heat pumps shown have varied heat production (particularly air-to-air) because temperatures from which the heat is drawn can vary, sometimes dramatically. The numbers shown are close to best case. The last four fuel sources all have to be combusted in order to yield heat to your home (and sometimes your hot water). They are all burned in some kind of furnace or appliance. Combustion efficiency comes into play in determining the net cost/MMBTU produced. The likely best case for combustion efficiency of those four is shown below:

|

Combustion fuel type Efficiency (%)

Natural Gas 93 Propane Gas 93 Fuel Oil 90 Commercial softwood or hardwood (EPA-rated) 70 |

These are the BTUs that can be gained from burning a unit of the fuel type listed. If this heat travels through ductwork in the home, there will be additional losses on the way to its delivery point. |

The table below shows the heating fuel, the units in which it is sold in the retail market, the approximate efficiency of this fuel when converted for household use, the net units to produce one million BTUs before any ductwork, the approximate cost of the fuel as of Fall, 2011, and the net cost per million BTU delivered to the home or its ductwork. The formula to calculate these values follows underneath the table.

*The cost per unit of electricity shown is the first tier price of Pacific Gas & Electric's baseline allowance of 906 kwh/mo in Quincy, CA. Those using more monthly electricity will pay more. Greater analysis of this will be found below, in the area marked as GSHP (ground source heat pump) operating costs with electricity from either of two utilities.

*The cost per unit of electricity shown is the first tier price of Pacific Gas & Electric's baseline allowance of 906 kwh/mo in Quincy, CA. Those using more monthly electricity will pay more. Greater analysis of this will be found below, in the area marked as GSHP (ground source heat pump) operating costs with electricity from either of two utilities.

Table of fuel costs per delivered million BTUs--

Fuel Type Units as sold %Efficiency net Units/MMBTU Cost / Unit Net Cost / MMBTU

|

|

The formula for the math (above)

1,000,000 ÷ BTU/unit ÷ efficiency (decimal) = number of units | # of units x unit price = net cost per million BTUs

1,000,000 ÷ BTU/unit ÷ efficiency (decimal) = number of units | # of units x unit price = net cost per million BTUs

Energy Costs for a home @3,500 feet in the Northern Sierra Nevada Mts. of California--

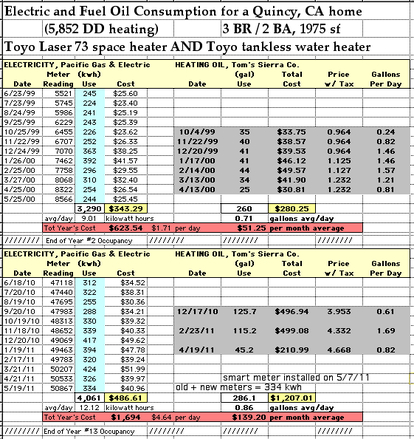

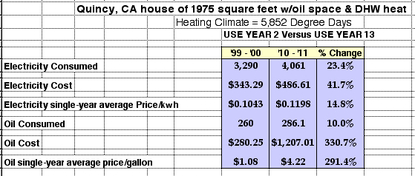

The data below compare the energy consumption and cost of a contemporary home built in 1998 in Quincy, CA, a community with an average heating climate of 5,852 degree days. The building is 1,975 sf, and contains R-38 ceilings, R-22 walls, R-19 floors, and has windows with a U-value of .48. It has a common north wall with its attached garage. Heating is accomplished by a direct-vent style, A-1 kerosene burning heater (Toyotomi Laser-73), driven by electricity for ignition and convective fan distribution of the combusted fuel. The heater has three levels of output between 15,000 and 40,000 BTU/hr, is thermostatically driven and has set-back timer options. Hot water is generated by a tankless, A-1 kerosene burning water heater (Toyotomi BS-36UFF) that uses electricity for ignition and exhaust evacuation. It produces a 60-80°F water temperature rise at flow rates between 3.5 and 2.7 GPM.

Since initial construction, the hot water delivery plumbing was modified with a pumped loop on a timer for the purpose of eliminating delays in obtaining hot water at distant use points from the tankless water heater. All lines are insulated. Total pump time is about 11 hours per day. The circulating pump consumes 45 watts.

While the argument can be made that this retrofit increased hot water thermal losses, it can also be said that wasted (now cool) water in the previous heated line (needing evacuation before hot water can again arrive at a point-of-use) has been reduced by elimination of wait times during the pumping schedule. Nevertheless, setting aside the vagaries of different weather during these two comparison years (2010-11 was a longer and colder winter), oil consumption is definitely higher.

The property's electricity use is also up. This might be due to many possibilities; among them are greater use of outdoor holiday lighting, addition of a large shop-RV bay in the backyard with battery charging and some refrigeration, and greater electricity use to power more cycling of the direct-vent oil heater in the colder weather of 2010-11.

Since initial construction, the hot water delivery plumbing was modified with a pumped loop on a timer for the purpose of eliminating delays in obtaining hot water at distant use points from the tankless water heater. All lines are insulated. Total pump time is about 11 hours per day. The circulating pump consumes 45 watts.

While the argument can be made that this retrofit increased hot water thermal losses, it can also be said that wasted (now cool) water in the previous heated line (needing evacuation before hot water can again arrive at a point-of-use) has been reduced by elimination of wait times during the pumping schedule. Nevertheless, setting aside the vagaries of different weather during these two comparison years (2010-11 was a longer and colder winter), oil consumption is definitely higher.

The property's electricity use is also up. This might be due to many possibilities; among them are greater use of outdoor holiday lighting, addition of a large shop-RV bay in the backyard with battery charging and some refrigeration, and greater electricity use to power more cycling of the direct-vent oil heater in the colder weather of 2010-11.

Your host is on record elsewhere on this Web site as favoring the ground source heat pump. A reason for this is connected to the tables and the math (above). A future scenario of price increases for all fuels of 10% will not raise the net Cost/MMBTU equally among them. The majority of the heat provided by heat pumps comes from air or underground sources. The electric energy used to capture it just operates the system. Electric power does not MAKE the heat; it just transfers and concentrates it. Therefore, in a theoretical fuel cost rise of 10% the equivalent rise in electricity cost to do your heating will be reduced by 25-33% (the percentages corresponding to COPs of 3.0 and 4.2, above). COP = Coefficient of Performance, comparing heat pump performance to straight electrical resistance.

The spreadsheets below analyze how a ground source heat pump system would perform against three common fuel types for both electrical utilities serving the Plumas County, California area

|

Operating cost estimates for GSHPs running at 4.0 COP using electric power from Pacific Gas & Electric rates against Oil, Propane, and Wood. <click thumbnail for larger image>

vs Oil vs Propane vs Wood

|

Operating cost estimates for GSHPs running at 4.0 COP using electric power from Plumas-Sierra R.E.C. rates against Oil, Propane, and Wood. <click thumbnail for larger image>

vs Oil vs Propane vs Wood

|